Worldwide restrictions during the Covid-19 pandemic caused huge reductions in travel and other economic activities, resulting in lower emissions, showing how closely climate warming and air pollution are linked.

In a new study, using satellite data from NASA and other international space agencies, scientists offered insights into addressing the dual threats of climate warming and air pollution.

“We’re past the point where we can think of these as two separate problems,” said lead author Joshua Laughner, a postdoctoral fellow at Caltech in Pasadena, California.

“To understand what is driving changes to the atmosphere, we must consider how air quality and climate influence each other.”

The paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that while carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions fell by 5.4 per cent in 2020, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere continued to grow at about the same rate as in preceding years.

Using data from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 satellite launched in 2014 and the NASA Goddard Earth Observing System atmospheric model, the researchers identified that while the drop in emissions was significant, the growth in atmospheric concentrations was within the normal range of year-to-year variation caused by natural processes.

Also, the ocean didn’t absorb as much CO2 from the atmosphere as it has in recent years — probably in an unexpectedly rapid response to the reduced pressure of CO2 in the air at the ocean’s surface.

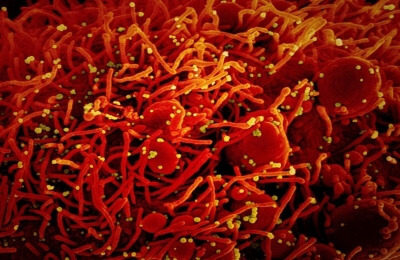

Further, the pandemic-related drops in Nitrogen oxides (NOx) quickly led to a global reduction in ozone — a danger to human, animal, and plant health. NOx in the presence of sunlight can react with other atmospheric compounds to create ozone.

Reducing NOx emissions was not only beneficial in cleaning up air pollution, but it also limited the atmosphere’s ability to cleanse itself of another important greenhouse gas called methane, the researchers said.

Although estimates of how much methane emissions dropped during the pandemic are uncertain because some human causes, such as poor maintenance of oilfield infrastructure, are not well documented, but one study calculated that the reduction was 10 per cent, the team said.

However, as with CO2, the drop in emissions didn’t decrease the concentration of methane in the atmosphere. Instead, methane grew by 0.3 per cent in the past year — a faster rate than at any other time in the last decade. With less NOx, there was less hydroxyl radical to scrub methane away, so it stayed in the atmosphere longer.

Notably, emissions returned to near-pre-pandemic levels by the latter part of 2020, despite reduced activity in many sectors of the economy.

“This suggests that reducing activity in these industrial and residential sectors is not practical in the short term” as a means of cutting emissions, the study noted. “Reducing these sectors’ emissions permanently will require their transition to low-carbon-emitting technology.”