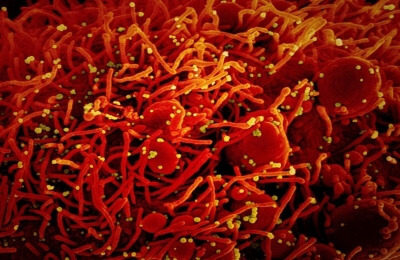

Malaria is typically known to cause a blood and liver infection. But, a new study detected antibodies primarily made in response to infections in the mucous membranes — lungs, intestines, or vagina — among malaria patients.

According to researchers from the University of Maryland, the finding provides new insight into how the human body responds to malaria infection and may ultimately help to identify new ways to treat malaria or develop vaccines.

In the study, published in NPJ Vaccines, the team looked at antibodies collected from the blood of 54 adult research participants after being infected with malaria in the laboratory — either through an IV inserted directly into the blood or through mosquito bites.

They also examined samples of blood taken from 47 children living in Mali, West Africa, who were enrolled in a malaria vaccine trial and acquired malaria during the study period.

Researchers detected high levels of IgA antibodies in the adult participants infected with malaria. In addition, 10 of the children had levels of IgA antibodies similar to those of the adults tested.

“We do not know what triggers the IgA antibodies to develop, but we think it happens early in a malaria infection,” said paediatric infectious disease physician Andrea Berry, Associate Professor of Paediatrics at the varsity’s school of medicine.

There are several possible explanations for this difference between the adults and the children.

“Perhaps, children’s immune systems respond differently to the parasite than adults do, or it is possible that IgA antibodies are only created during the first malaria infection,” Berry said.

She explained that in the adult participants, researchers knew that they received their first infection, but whether the children had been previously infected was unknown.

The timing of the infection and sample collection was uniform among the adult study participants, but not with the children, because their malaria infections were coincidental during the study.

Berry said they can now test to see if IgA antibodies prevent malaria parasites from going into the liver or red blood cells. They can also investigate which proteins in malaria these IgA antibodies target and whether they would be good candidates to use in a vaccine.

Even with medical advances, malaria remains one of the leading causes of death in developing countries. More than 400,000 people die each year of malaria infections, with more than two-thirds of these deaths in children under 5 years old, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).